Ohio River Boulevard

Ohio River Boulevard

One of the most scenic ways to enter the City of Pittsburgh, Ohio River Boulevard has had a short, but interesting history. Proposals for an expressway on the North Side were plentiful in the 1960s. Three routes were selected to be studied further:

Two forces came to battle over which alternative should be used. The Department of Highways favored the Upper Route whereas the North Side Civic Promotion Council leaned towards the Lower Route. In a statement about the Commonwealth's preference, the NSCPC said, "The Ohio River Boulevard route as announced by the state will create an intolerable situation on the North Side. Not only will it split one of our greatest assets but will utterly destroy a desirable residential area north of North Avenue which has great possibilities for rehabilitation and future development." Faced with alienating an entire neighborhood, the Department of Highways changed their preference and began planning the Lower Route.

Ideas for the expressway were already being drawn up in 1967 with the median being one of the important parts of the project. Typically, an urban expressway consisted of a raised curb with a guardrail mounted on top. The Ohio River Boulevard expressway would have a planter box to separate the opposing lanes of traffic and would be 30 inches high and 20 feet wide containing a mix of sod, Washington Hawthorne trees, and nannyberry shrubs. Mayor Joseph M. Barr felt that this idea would be beneficial in three ways: deterring crossover accidents, eliminate headlight glare at night, and relieve the usual bland appearance of an expressway, making it easier for the neighborhood to live with the highway. Another feature of the median is that the outer walls would be extended outward at eight different locations to create more planting boxes that would contain Pin Oak shade trees and shrubs. The $300,000 experimental medial planter box would be used on a 1,600-foot section of the two-mile expressway, and if proved successful, would be incorporated into other Department of Highways expressway projects planned for Pittsburgh. "We felt strongly that, as a major portal to the city, this expressway should be given special landscaping consideration," Mayor Barr said. "The team engaged in this experiment found that the objectives of beauty and safety can be one and the same."

As 1967 went on, talk soon moved from the look of the expressway to the cost. On May 22, Mayor Barr announced that the city would pay $750,000 as its share of cost for the new highway, which was a price negotiated with the Department of Highways. With the agreement in place, the department could begin to advertise for bids the following month on the first phase from North Avenue to Adams Street. This also included reconstruction of Chateau Street which runs on the eastern side of the expressway. The city's share for the right-of-way acquisition for the entire project would be approximately $575,000 and $150,000 for the landscaped median that would include lighting, curb work, and other improvements. The second phase of work would include the construction from Adams to Superior Avenue and the final phase would link the expressway with the Fort Duquesne Bridge and ramps.

The expressway came closer to construction on June 16, 1969, when the Department of Highways submitted the plans for the project to the United States Bureau of Public Roads, predecessor to the Federal Highway Administration. Department of Highways Secretary Robert Bartlett said that the project could not be advertised for bids until it was reviewed by Federal engineers and approved by the bureau. City traffic engineer Anthony M. Miscimarra said the city and Department of Highways still had issues that would arise during construction to resolve. He said for the first year construction, traffic would be maintained on Ohio River Boulevard, Marshall Avenue, and the Island Avenue Bridge into the Manchester area of Pittsburgh.

A wrench got tossed into the plans on June 25, 1969, when Pittsburgh City Council learned that the Department of Highways expected the city to pay 100% of relocating water lines for construction of the expressway. The Commonwealth served notice that it needed a letter of intent from the city regarding costs of relocating water lines, plus sharing costs of curbing and sidewalk construction before work could begin on phase two of the project. No letter could result in the project being held up for a year, the state warned. Councilman J. Craig Kuhn called the state's position "holding a gun at the city's head." He wasn't pleased when presented with a "bill" for $317,000, which was the state's estimate for the city's share of the project His disposition grew more indignant when told that the state's share would come from federal grants, which the city would not get to touch to meet its share. The cost for replacing water lines came to $95,000 and was called "unprecedented" by Water Department Director William Clair. He said that it constituted 100% of the costs of relocating the lines and that the city had never paid that much. He pointed out that the city supplied 50% of the funds on city and/or state projects and only 10% on federal projects. Kuhn declared that the city could not afford to meet the high costs and accused the Department of Highways of hoarding federal money and spending it in rural rather than urban areas.

Construction began on the $21 million expressway from the Fort Duquesne Bridge to Ridge Avenue in 1968, as a part of the North Shore revitalization project which included the former nearby Three Rivers Stadium. This section opened to traffic in 1970, and includes the only mid-air interchange in the Pittsburgh area at Interstate 279. A temporary connection was made at Ridge Avenue to provide an outlet for traffic to use and a reason to open the Fort Duquesne Bridge, thus making the "Bridge to Nowhere" finally go somewhere. This temporary interchange would last until 1992.

Construction would being on the next section of Ohio River Boulevard from near the California Avenue/Marshall Avenue intersection to Pennsylvania Avenue in January 1970. E. J. Albreeht Company of Chicago was the lowest bidder for the expressway project and associated lighting work which totaled $16,152,000 and was the second-largest single bid in District 11. The largest bid was for the I-79/Parkway West interchange near Rosslyn Farms. The reason for the high cost was because of the complicated engineering requirements and it traversing an urban area. In 1973, this $16 million section opened to traffic with plans to continue the expressway to the Fort Duquesne Bridge. However, this plan was in its infancy, and partially stalled by indecision over whether to rebuild the West End Bridge or replace it with a twin span crossing.

One of the most unusual plans in this part of the project was the idea to use artificial turf for landscaping. Costing $25 per square yards, about 890 square yards of synthetic grass were included in the project. PennDOT officials said that this would be the first use of this turf in highway construction in Southwestern Pennsylvania. It would be placed where elevated ramps join and planting grass is impractical, and in places underneath the elevated expressway where lack of sun and rain will not permit natural growth. Another unique feature is that the 81-foot wide concrete deck is supported by web-like steel flanges cantilevered on central support beams about 10 feet high. The reason for the height was because the expressway crosses rail lines at the California Avenue/Marshall Avenue intersection.

Movement on the expressway began to happen on October 12, 1979, when from beneath an approach to the Fort Duquesne Bridge, Governor Richard Thornburgh said that the link would be finished by 1986. In the race for governor, both Thornburgh and his defeated opponent, former Pittsburgh Mayor Pete Flaherty, campaigned vigorously on the idea of completing the "missing" expressway links in Western Pennsylvania.

After seven years of the plans to connect the two sections of expressway being shelved, PennDOT began to blow the dust off them in December 1980. The area of the expressway had become an eyesore of empty lots, vacant buildings, rubble, and vandalism since construction began on Ohio River Boulevard in the early 1970s. The Federal Highway Administration authorized nearly $7 million to buy property in the dilapidated right-of-way. The money would be used for "hardship cases" only, but any property owner could sell to PennDOT. Pittsburgh was the second place in the country where the FHWA agreed to a wholesale method of buying land before the environmental impact statement and highway design was finished, and before a commitment to build was made. The money was transferred from funds allocated for a Penn-Lincoln Parkway/Crosstown Boulevard interchange, plans which PennDOT abandoned in 1979.

The agreement came after months of intensive lobbying in Washington by top PennDOT officials, then state Representative Tom Murphy of the North Side, who would later become Mayor of Pittsburgh, and Stanley Lowe, executive director of the Manchester Citizens Corporation. Murphy said, "Right now, PennDOT will be cleaning up the area and helping the people who have been trapped in the bureaucracy for all these years. It's criminal that PennDOT has left the property owners in that position in the first place...Because of the blighted conditions and hardships suffered by property owners, it was important to take some action now and not two years in the future."

Even though this money would be available to clean up the mess in Manchester, it didn't meant that construction would continue on the expressway. Roger Carrier, PennDOT District 11 engineer said, "There is no way we (PennDOT) have enough money to build all of the missing links in Pittsburgh. The appropriate government officials will have to decide what they want, what should com first." The latest estimate for construction had brought the price tag to above $50 million. Meanwhile, PennDOT marked out a "sure take area" which consisted 36 occupied homes, 60 vacant dwellings, 23 commercial or industrial buildings, and 123 vacant lots. This area comprised structures and land that would definitely be needed to build the expressway from the initial plans.

Things started swinging into action in 1982, when on March 31 the first public meeting was scheduled to discuss the expressway. "A lot of things delayed it, but what delayed it most was a dream about replacing the existing West End Bridge with twin bridges," said Rudy Melani, PennDOT District 11 design liaison engineer. He said the elaborate scheme proposed big interchanges that "would have wiped out half of the West End and half of Manchester," and produced the most expensive bridge-highway project in Western Pennsylvania history to that date. Melani said, "We'll never build twin bridges across there, because there's not that kind of money available. Our latest design does not include a new West End Bridge." The plan did eliminate some of the frills and missed a designated historical district in Manchester. This was the last chance to build the expressway because the Federal Highway Administration decreed that interstate projects not under construction by 1986 would not be eligible for funding. Melani said PennDOT hoped to hold a formal, mandatory public meeting in August and have the environmental impact statement approved and signed by the end of the year. The latest design called for 10 lane miles (one lane of highway one mile long constitutes a lane mile) of highway, some new and some rebuilt and only replacing the portion of the West End Bridge from the north shore of the Ohio River to Western Avenue.

Pressure to finish the missing section came on May 6, 1985 when a 21-ton truck flipped over and landed onto a Salvation Army van with four passengers at the sharp bend on the temporary ramp at Ridge Avenue. Luckily, all those involved in the accident survived with only minor injuries. PennDOT traffic engineer Thomas Fox said he would study the police report to determine if any addition signs to the two already posted, should be erected to warn truck drivers to slow down as a stop-gap measure. As for the completion of the expressway, Donald Childs, PennDOT assistant district design liaison engineer said, "We're hoping to complete the designs by next year at this time. It will be a two-year construction job and we're hoping by the end of 1988 to have it completed." He added, "This Ohio River Boulevard project is getting the same attention as completion of the East Street [Valley Expressway] project because it will become an integral part of the Interstate system as a major feeder highway."

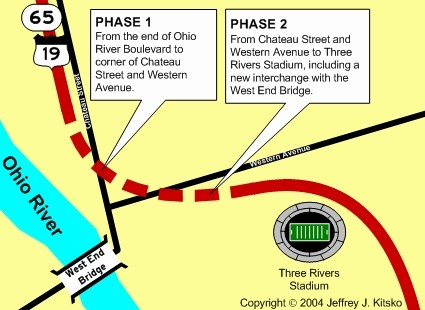

With traffic increasing on the North Shore, construction on the $8 million Phase One project to connect the two sections of Ohio River Boulevard together began in Spring 1987 from Allegheny Avenue to Western Avenue. Phase Two of the project would begin in January 1988, which would consist of a new interchange between the expressway and the West End Bridge. The bridge would be closed for two years while it underwent rehabilitation and new ramps were built at the northern end for the interchange.

Area of the missing-link which was completed.

On January 14, 1992, the project finished 40 years after first being planned and opened to traffic for that day's afternoon rush hour. With the new expressway opened, the temporary interchange at Ridge Avenue was eliminated. Dick Enterprises, now Dick Corporation, the contractor for the project, finished the $45 million West End project which included rehabilitation of the West End Circle and Bridge ten months ahead of schedule. The bridge reopened three months earlier than the projected 16 months in July 1991.

A $9.4 million reconstruction project at the Ohio River Boulevard/Marshall Avenue interchange in Pittsburgh began on July 22, 2010. Phase I included redecking of the ramp from the northbound direction of the expressway and Chateau Street to Marshall Avenue which was completed in November 2010. Phase II began on July 15, 2011 with the closure of the bridges carrying Ohio River Boulevard over the Marshall Avenue interchange for rehabilitation, and the $20 million phase was completed in November 2011. Phase III began on January 21, 2013 and included rehabilitating two structures over the Norfolk Southern Railroad line. The $14.2 million phase was completed in Fall 2013 marking the end of the project.

|

In the 1963 Pittsburgh Area Transportation Plan,

provisions were made to build this expressway all the way to the then

proposed Interstate 279, now designated Interstate 79, near Glenfield.

The project, like many others proposed at that time, were killed in the

1970s. Interchanges would have been built at the following locations:

|

Links:

Exit Guide

Ohio River Boulevard Pictures

PA 65

Ohio River

Boulevard - Adam Prince

PA

65 Junction List - Tim Reichard

Terminus

of PA 65 - Adam Prince

INFORMATION

INFORMATION |

| Southern Terminus: | I-279/Truck US 19 in Pittsburgh |

| Northern Terminus: | McKees Rocks Bridge in Pittsburgh |

| Length: | 3.21 miles |

| National Highway System: | Entire length |

| Name: | Ohio River Boulevard |

| SR Designations: | 0065 0019: West End Bridge to Marshall Avenue |

| County: | Allegheny |

| Multiplexed Route: | US 19: West End Bridge to Marshall Avenue |

| Former Designations: | None |

| Former LR Designations: | 1039: Fort Duquesne Bridge

to Allegheny Avenue and North Avenue to Marshall Avenue 652: Marshall Avenue to the McKees Rocks Bridge |

Washington's Trail: |

Entire length |

| Emergency: | 911 |